News

NewsMarco Awad, Assistant Editor-in-Chief | September 11, 2025

A&E

A&EAlice Li, Copy Editor | September 11, 2025

A&E

A&EJenny Navar, Staff Reporter | September 3, 2025

News

NewsLauryn Desai, Student Life Editor | August 27, 2025

Apple’s much-anticipated “Awe Dropping” fall keynote on Sept. 9, 2025 delivered a wave of major product announcements that have tech fans...

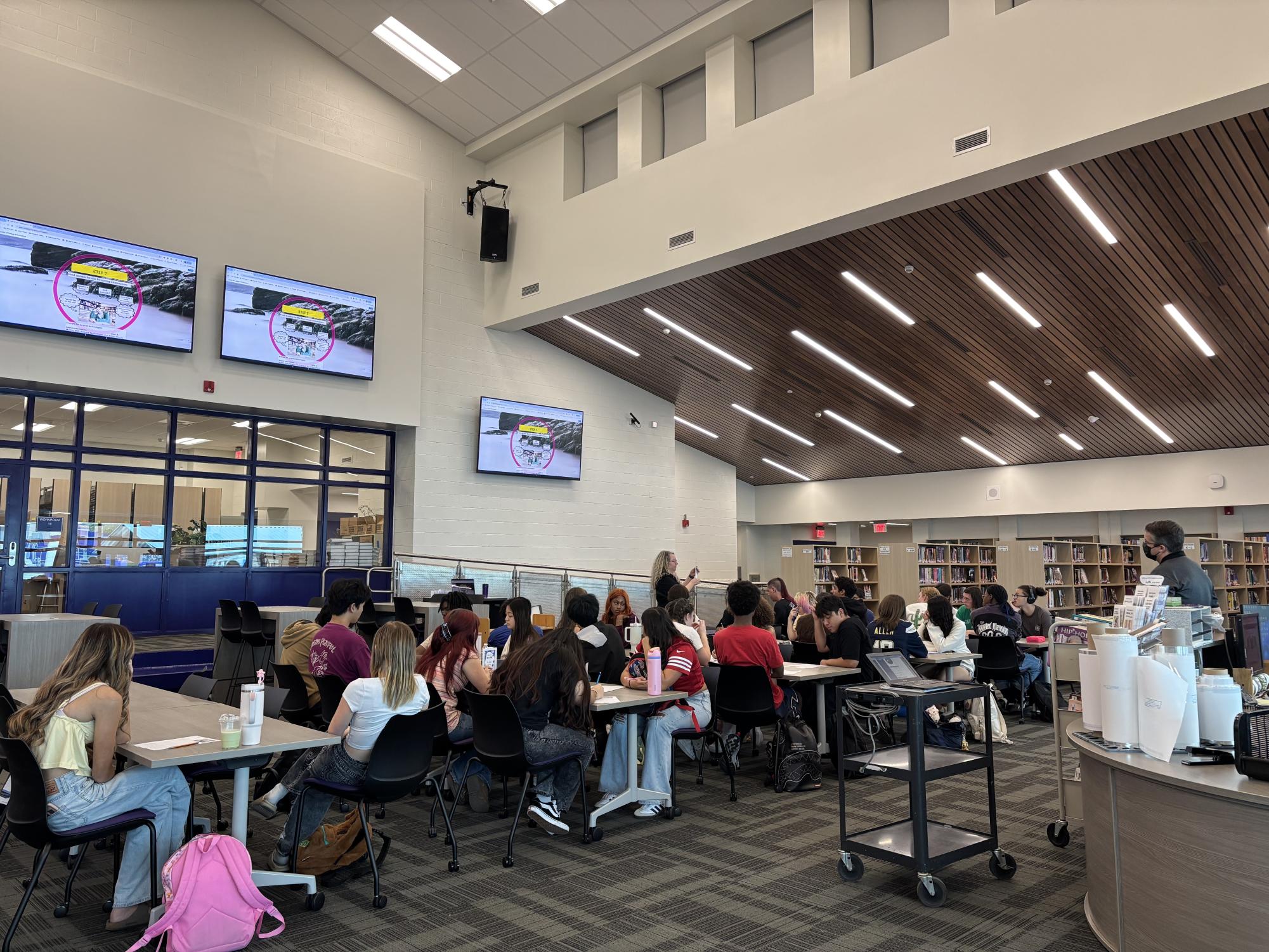

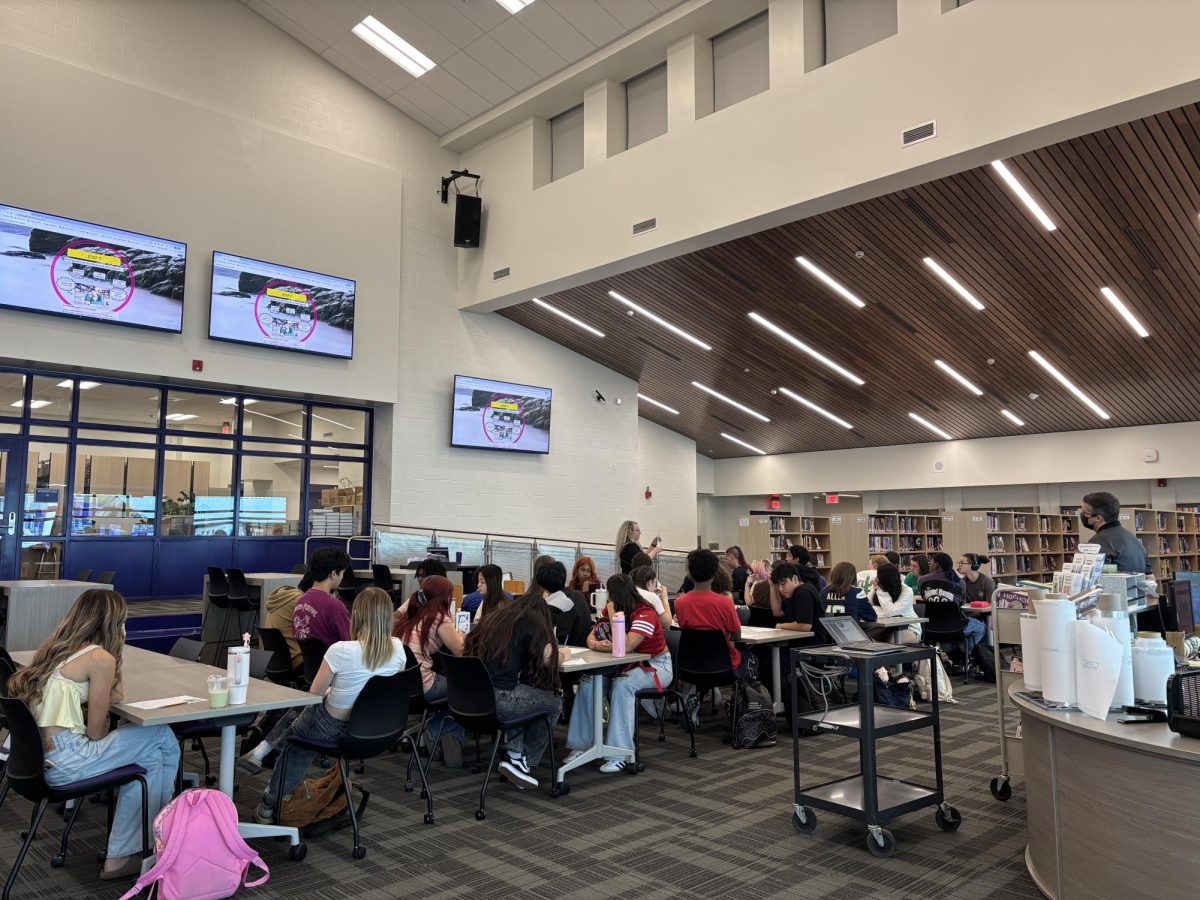

The new Rancho Cucamonga High School library celebrated its official grand opening on Thursday, Sept. 4. Before the official grand opening, the...

Rancho Cucamonga High School celebrated its annual Homecoming Spirit Week Sept. 8 to Sept. 12, leading up to the Homecoming dance on Saturday,...

From dealing with a big campus, to seeing many new people, freshman year might be challenging for some. To help freshmen feel more comfortable...

Digital film is an influential program at Rancho Cucamonga High School. With its bulletin airing multiple times a week and participation...

For the first week of the NFL season, the reigning 2025 Super Bowl champions, the Philadelphia Eagles, and the Dallas Cowboys went against each...

The Rancho Cucamonga High School football team defeated Oak Hills High School 14-3 in its first home football game of the season on Friday, Sept....

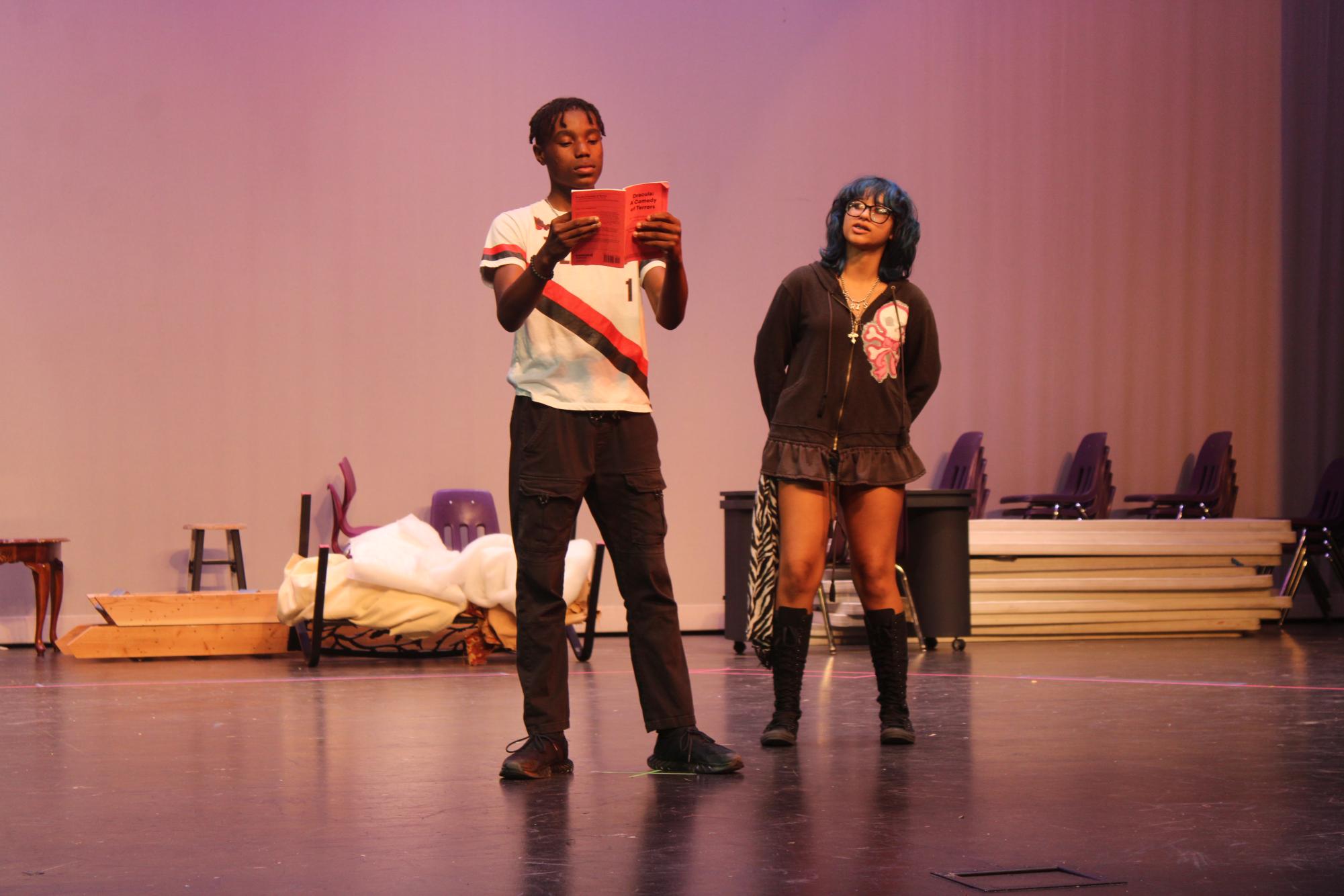

This fall, Rancho Cucamonga High School’s Visual and Performing Arts programs will perform what they’ve learned for friends, family, and...

The classic blue and grey batsuit isn’t the only thing that Matt Fraction and Jorge Jiménez are changing in Batman’s world. Batman #1 was...

Fashion is always changing, and sometimes a little too quickly. Recently, fast fashion has been on the rise, with stores like Garage, Shein,...

Homecoming without a theme is like food without flavor. The theme allows the students to feel like they are a part of a limited-time event. This...