Breaking the cycle of generational trauma

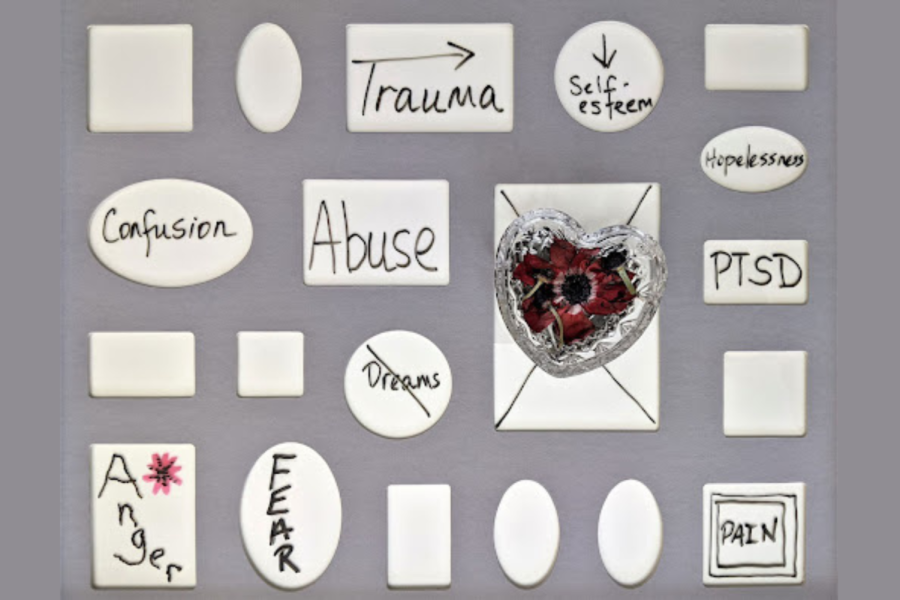

Photo courtesy: Susan Wilkinson

Gen Z” is a generation of true cycle-breakers as they realize unhealthy patterns and work to heal. Photo used with permission from unsplash.com.

Past generations came from times of war, oppression, brutality, and imperialism when survival was of utmost priority. Many immigrated to the U.S., working tirelessly to build the life they never had for their families. Their excruciating efforts pass like heirlooms, from grandparent to parent and parent to child, so the current generation may reap the benefits of wealth, success, and security.

Yes, previous generations may have succeeded in building stable lives. But they also carried with them the pain and suffering of the journey, left unresolved and suppressed for survival. Mistreatment was the norm at a time like that.

That trauma passes down and resurfaces from generation to generation through abuse and mental health issues, but Gen Z is breaking the vicious cycle of generational trauma.

As high school students, generational trauma becomes more and more prominent, especially at the crucial age of self-discovery. That trauma begins to explain unhealthy behavioral patterns and mindsets parents embedded in their children.

Now, high school students and Gen Z as a whole work to heal and break the cycle of trauma instead of passing it on.

What is generational trauma?

As defined by health.com, generational trauma is unresolved trauma that extends beyond one generation and resurfaces through patterns of different types of abuse and symptoms such as anxiety, hypervigilance, and depression that affect today’s generation.

An RCHS senior who wishes to remain anonymous described how generational trauma prevents her from being her true self.

She said, “I was never able to express myself or to wear what I want. I feel so controlled by my parents that it makes me feel like I’m drowning and is one of the reasons for my anxiety.”

This is because, she said, “My parents were raised in a certain country that really shaped their parenting style, especially in such a different generation.”

The origin of generational trauma is undefined, yet it seeps from countless sources and bleeds into almost every aspect of daily life.

Ariana Aldon, a professional school psychologist at Norco Intermediate School, said, “There’s so many ways to look at it. There’s the generation they were born in and what’s going on with those parents at that time, but we could also look at gender and culture, religion, and even poverty.”

Disney’s animated feature film Encanto illustrates generational trauma. Mirabel’s grandmother Alma Madrigal fled her burning hometown with her children after her husband was murdered. She raised her children as hard workers to keep herself and the so-called “miracle” from collapsing.

However, she focused more on her family’s reputation than her children’s well-being, even pushing away her own son.

Hence, she raised the next generation of children with extreme pressure regardless of their role, all to satisfy Alma. It isn’t until Mirabel identifies this issue that Alma realizes her grave mistake: she has denied her fault in projecting her unresolved trauma upon her family, causing deep-rooted damage.

Encanto is a perfect example of how trauma, be it cultural, religious, or historical, transpires over generations, leaving the youth to confront the issue and make a difference.

My own ancestors lived through times of war and calamity. Born and raised in Pakistan, they faced bombings and tremendous amounts of death and brutality. That severe PTSD associated with living in a war-torn country influenced their parenting, so my parents grew up not knowing how to express their emotions. In turn, I face anxiety from the lack of boundaries, understanding, trust, and empathy when in conflict with them, which then translates to other relationships in my life. This is generational trauma.

As Aldon mentioned, poverty also plays a role in generational trauma and its development within teens.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network reported that children raised in poverty by adults with histories of domestic violence struggle with emotional regulation, maintaining healthy relationships, and making sound financial decisions. All of these struggles may impair parenting and translate into the next generation.

Generational trauma stemming from poverty is damaging and becomes more of an issue as teens enter adulthood.

Aldon has worked with children in various environments throughout her career, including those in poverty.

“With families that I’ve seen, they put their own cap because of their own trauma and there’s no looking beyond that,” said Aldon. “There was this one kid who his family lived off of welfare and the principal asked why he doens’t get good grades. His response was ‘what’s the point when I’ll be living off of the government.’ And who is putting that cap on them? Their own family, for not telling them that they could do better.”

Aldon observed that adolescents who grew up in poverty became complacent, denying that their situation was unhealthy and refusing to make that change. That is the most dangerous part of generational trauma. It is so ingrained that it is normal.

“That behavioral component of generational trauma is really strong and can cause so much damage,” Aldon said. “When you see someone, you have to ask ‘where did that come from?’ To them, it’s normal.”

Another anonymous RCHS student demonstrated this within his own family regarding relationships. He said, “My parents grew up with very toxic views about relationships, and seeing how it later affected my family, I grew distant from everyone else in fear that I would make the same mistakes.”

All this said, two aspects set the current generation apart from previous generations: acceptance and awareness.

Aldon said, “This generation is more aware of mental health issues because my generation started talking about it, and the current generation has expanded on it.”

Much of this is due to social media and teens having more access to knowledge about mental health, which allows the youth to accept others while understanding that what they are experiencing themselves is not healthy. For an in-depth discussion of social media and mental health, see The Cat’s Eye reporter Lucianna Martin’s story “Mental health: The star of the 21st century.”

“People are more open nowadays,” Aldon said. “You have a better understanding of the full scope of a story instead of going off of biases, which is what former generations go off of.”

The power to break the cycle of generational trauma grows within today’s high schoolers’ hands because they are not only aware of generational trauma but also work to normalize therapy and advocate for mental health resources.

With increased awareness of mental health relating to trauma through means such as social media, Gen Z is the generation to finally break the cycle.

Moreover, teens who know about generational trauma actively work to improve themselves first to improve the lives of others.

“I’m breaking the cycle by taking into account my own self-love above all else,” said an RCHS sophomore. “I now realize that a healed and fulfilled soul brightens just about every aspect of my life even beyond my relationships.”

After learning about generational trauma, more and more adolescents took it upon themselves and chose to end the trauma instead of passing it on.

One of the best steps I have taken for my own well-being is opening myself up to resources.

RCHS normalizes therapy and provides several accessible services geared toward student mental health, including partnerships with South Coast Community Services and many more.

South Coast Community Services is just one program that offers students free and anonymous counseling sessions. Moreover, the Wellness Center, located in room N201, is where students can go anytime for support.

Within my own life, validating my feelings and accepting therapy allowed me to realize that my response to conflict does not reflect myself, but rather the trauma that previous generations projected onto their children.

For example, I do not raise my voice because I am crazy, but because I feel unheard. Nor do I seek to please others because I want attention, but because I associate my security with the satisfaction of others instead of mine.

Now, I identify where my negative thoughts come from and why they exist, giving me a chance to improve myself as a daughter, a student, or even a leader.

For those who suffer the effects of generational trauma, that level of healing is the first step.

Aldon said, “You can break through that glass ceiling that you put on yourself. It’s not society putting a ceiling, it’s your own family. It’s important so you don’t stay within that range of ‘it’ll get a little better or get worse.’ It truly is a holistic approach to becoming a better person.”

Nimrah Khan is a senior at RCHS, and this is her third year in journalism. She is the editor-in-chief of the school newspaper, The Cat’s Eye. Her favorite...